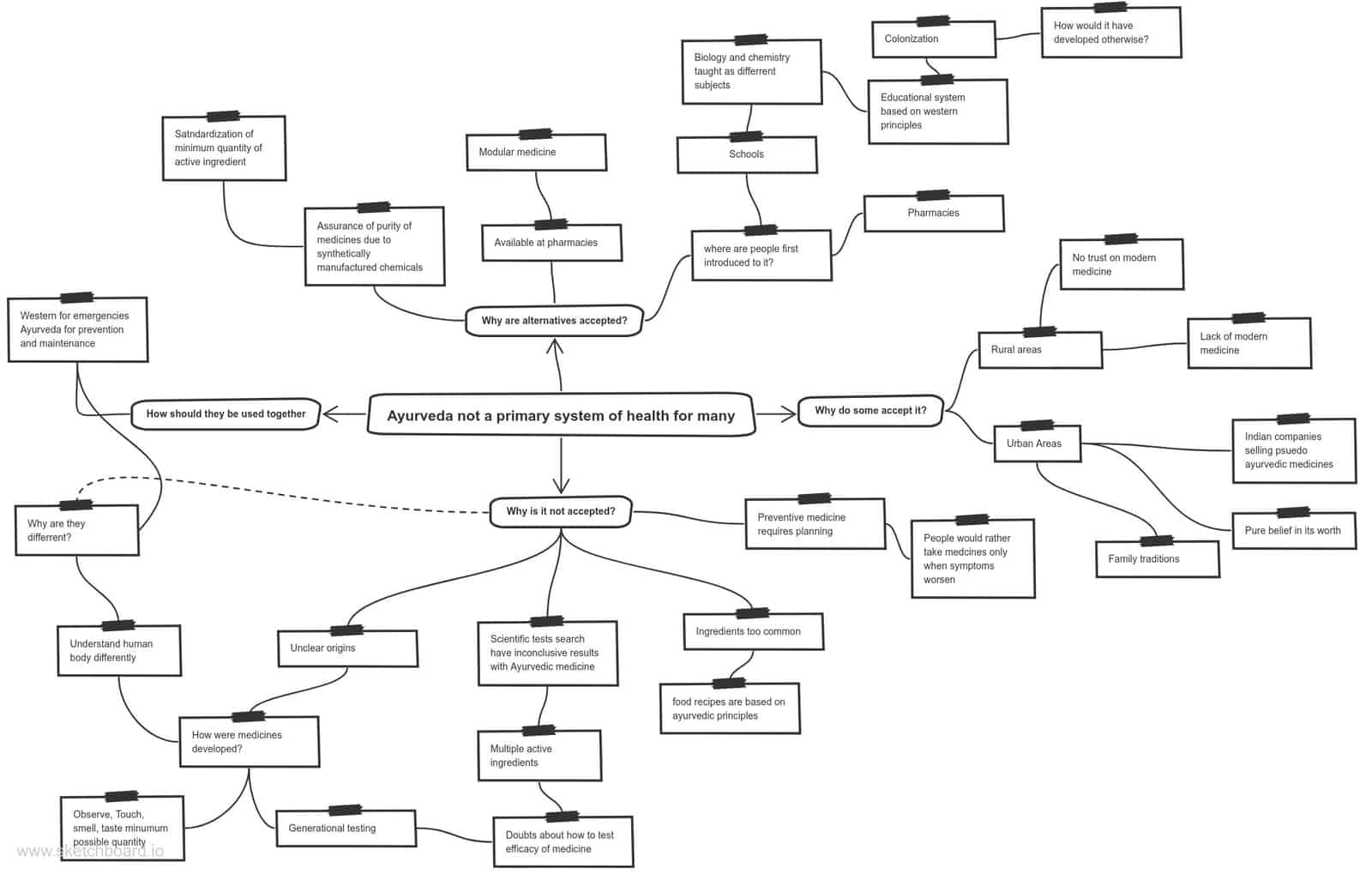

This absence of past research data on the development of the science, and majority of people who have been educated through a different philosophy of knowledge than what Ayurveda is based on, has led this system of health to be ridiculed as superstitious and ineffective when it is not so.

A mind map to understand possible reasons

Having realized this problem, I collaborated remotely with a friend of mine, Dr. Eeshani

Bendale, an Ayurvedic practitioner and student in India, to apply innovation and design to

find new avenues for Ayurvedic researchers to explore. This would help the health practice

evolve to the stage at which modern medicine currently operates in India, in order to help

revive a culture which is on the verge of being lost.

This project was something I personally have wanted to work on for the past few years, but

never had a platform to do so before studying design. We used different user centered,

speculative and service design methodologies to understand problems, define the strategy,

and create a thought experiment to help researchers experiment in new ways.

Offering these solutions implied a cultural shift which would impact several businesses and

health practices. Using design to innovate was a fundamental change for Ayurvedic health

practitioners, it meant moving from proving that traditional medicines worked using

contemporary research protocols, to developing new research methodologies specific to

ayurvedic medicine and subsequently new information on how to better heal people.

Our approach was a 2 month deep dive into Ayurveda to understand the basics of the science. This involved studying the philosophies of Ayurveda, its history, current research methods, and understanding what doctors, patients, students and other stakeholders thought about it. This deep dive helped me understand basic diagnostic and treatment practices which my collaborator was already well versed with.

Involving the ayurvedic community during the design process paved the way for implementation. The

thought experiment was designed hand in hand with my collaborator from India . By working together,

we were able to leverage existing knowledge and understanding of Ayurvedic community and their

practice. We interviewed practitioners and students of both, modern medicine and ayurveda, mostly on

the phone or on messaging apps like Whatsapp. Interviews through messaging services gave better

insights than the ones on the phone. The extra time and space the interviewees had most likely

helped them reflect on the questions and articulate better in written form.

Additionally, involving different stakeholders through the service design process would reduce

resistance to change and facilitate implementation.

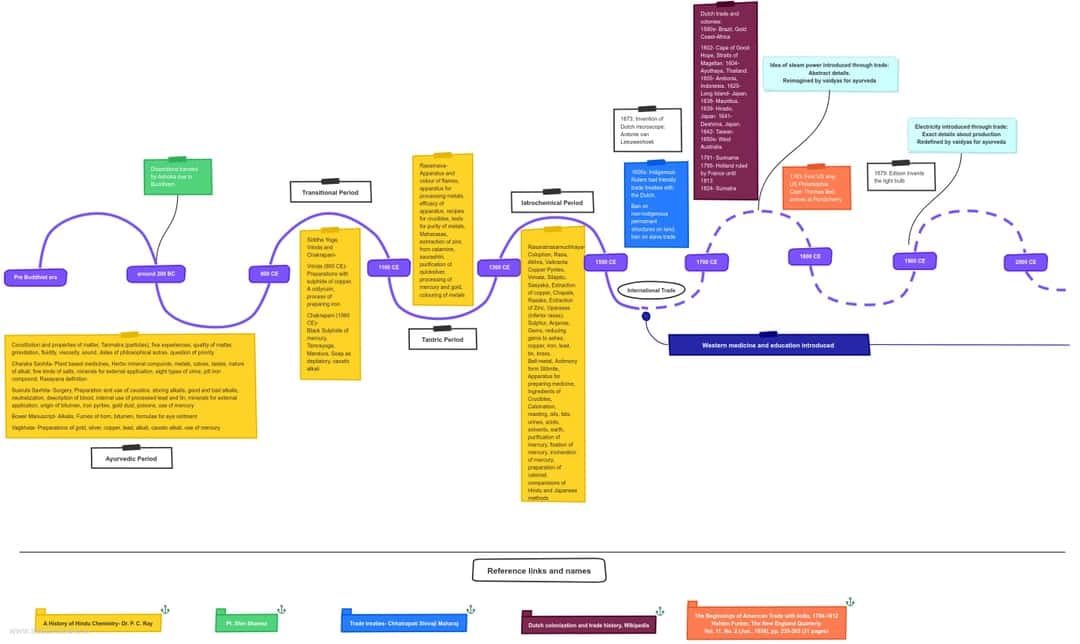

Studying the evolution of objects and their uses was the next step. We developed a process to simulate the evolution of medical devices after researching on how and why objects evolve. An instrument called patal koshti, used for processing zinc to make medicines, was taken through the timeline, incrementally modifying it to fulfill various requirements demanded from it at various stages in time, from the 1500s to the 2000s.

Prototyping this method allowed us to identify problems with this approach- this instrument

illustrated part of a vision for this alternate history, but was this process feasible for every

instrument?

Would speculation of this kind really be useful?

Evolving instruments in this manner, on pure speculation, would not be useful, given the intricacies

of creating medicines in Ayurveda, where every part of the instrument plays a physical and chemical

part in the process. It was the reason for the existence of these objects which needed to be

evolved, rather than evolving the instruments themselves in isolation.

Creating a workshop model for other ayurvedic practitioners and researchers made sense to get them involved. Leveraging the ridicule which Ayurveda faces in the Indian scientific would attract believers as well as skeptics to the table and start a discussion about what new can be done. Discussions like these needed to flow through the basic principles of Ayurveda, through a narrative of sorts, fluidly guiding researchers through the timeline, helping them explore. Such a narrative would also need to be falsifiable to harness ridicule, akin to a punching bag, which is intentionally made to be disproven in order to iteratively arrive at a new invention.

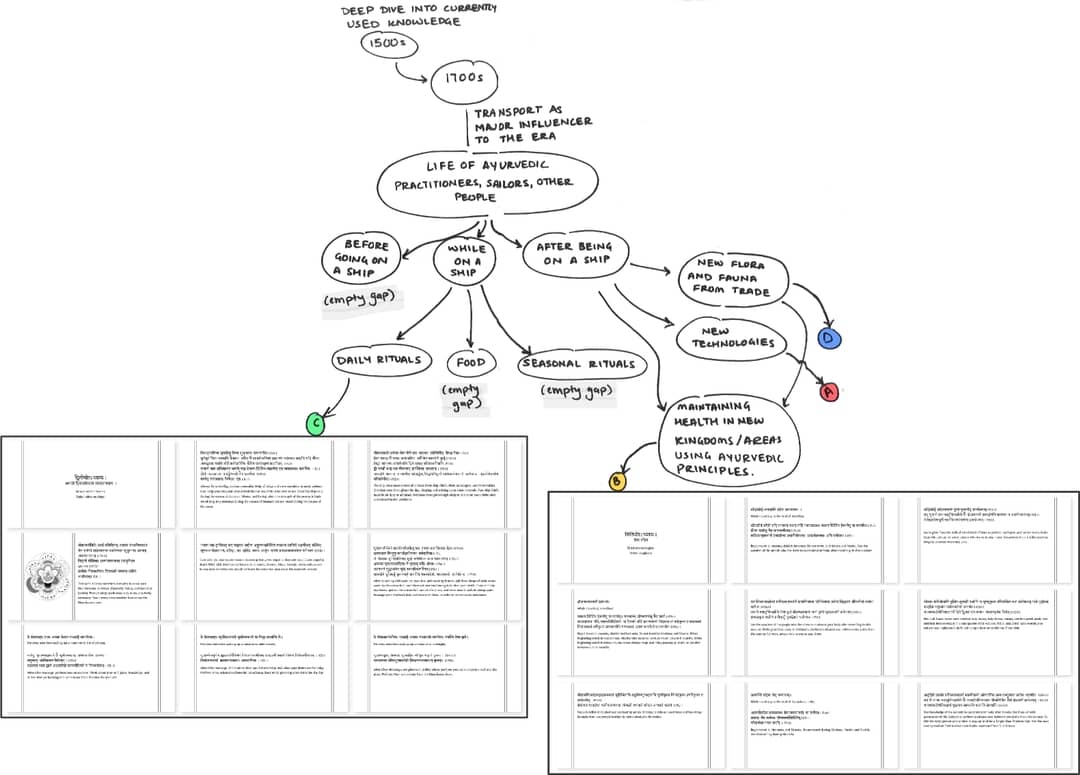

Choosing international trade and travel, we started exploring trade treaties and ship routes to get

an understanding of how international trade would have progressed in an uncolonized Indian

subcontinent. We developed empathy for Ayurvedic practitioners from the 16th Century, and tried to

research and imagine their lives before beginning a ship journey, while on board, and after reaching

a destination.

We then tried to understand how they would have maintained their health in these three situations,

what protocols they would have followed on these ships, and how new discoveries in these foreign

lands, relationships with natives, traded goods, and invention of new technologies would have been

assessed and adopted into Ayurveda.

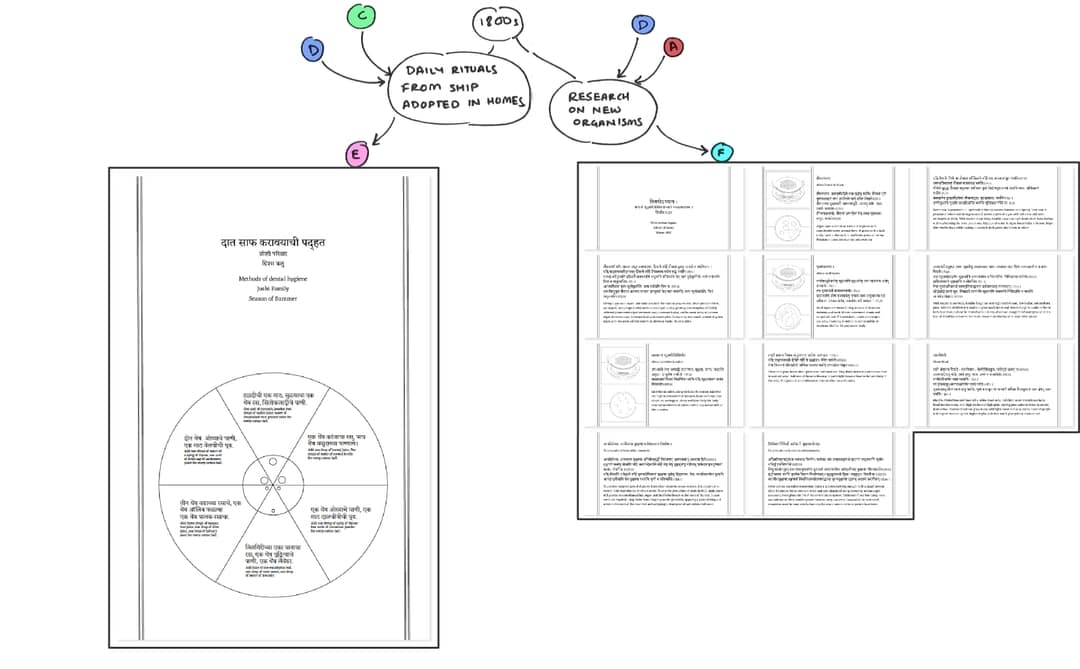

The narrative was written in the form of health practices which Ayurveda would have developed at different stages in this alternate history. It includes rules on planning ship journeys according to seasonal variations in health, recipes for maintaining good health onboard and in various foreign lands using locally available ingredients, adoption of the microscope into ayurveda in a modified form, and recipes for creating medicines using new technologies and instruments. The narrative has deliberate empty spaces for researchers to use their own imagination on, by taking cues from the main body.